En familiefest i fire scener – det er den rituelle ramme for Apollonian Blackout. Ceremonier, død og genfødsel i et krydsfelt mellem performance, koncert og installation. Først pumper en hjerterytme fra en trommemaskine, vibrerende 80’er-synth-frekvenser ulmer, mens John Carpenter scorer sin egen begravelse. Et stemningsfuldt anslag, der dog ikke når et fyldestgørende klimaks i sine melodiske forskydninger, inden tæppet falder, og man bevæger sig videre langs det spisebord, der er scenografiens omdrejningspunkt.

Musikere dukker op med slagtøj og akustiske streng- og blæseinstrumenter, eksperimentende, jazzet, groovy er det, og publikum inviteres til at udfylde pauserne med taktslag på bordets vinglas. Der chantes i tekstbidder – fragmenter fra generationers skåltaler væves ind i musiktapetet. Kærlighed, minder, længsel..

Det »transatlantiske ensemble« kan både være jamband og New Yorker-kantet som Laurie Anderson med hverdagslige og sloganklingende ordlyde. Stramt eksekveret men også legende som i cirkus med høje hatte og candyfloss som skrub-af-mad.

Der bydes op til dans, og trancen indfinder sig. Eskaleringerne muterer i dissonans og disciplineret polyrytmisk feberdrøm. Spisebordet udmunder i et ormehul malet på endevæggen; stedet hvor tiden strækkes og det lineære og cirkulære smelter sammen. Lidt for letkøbt højpanderi? Måske, men også en variation over Hess Is More’s udforskning af scenografiens materielle afsmitning på kompositionen fra forgængeren Apollonian Circles, som arbejdede med det cykliske. Apollonian Blackout undersøger, hvornår et konstant udviklende forløb bider sig selv i halen.

Trådene samles i festens rytmiske ophav – den afrocubanske musiks gyngende gentagelser. Beruset forlader man familiefesten, hyperopmærksom på kroppen, sanseapparatet og hjertets banken.

If John Malkovich could sing, it would be devilish singing

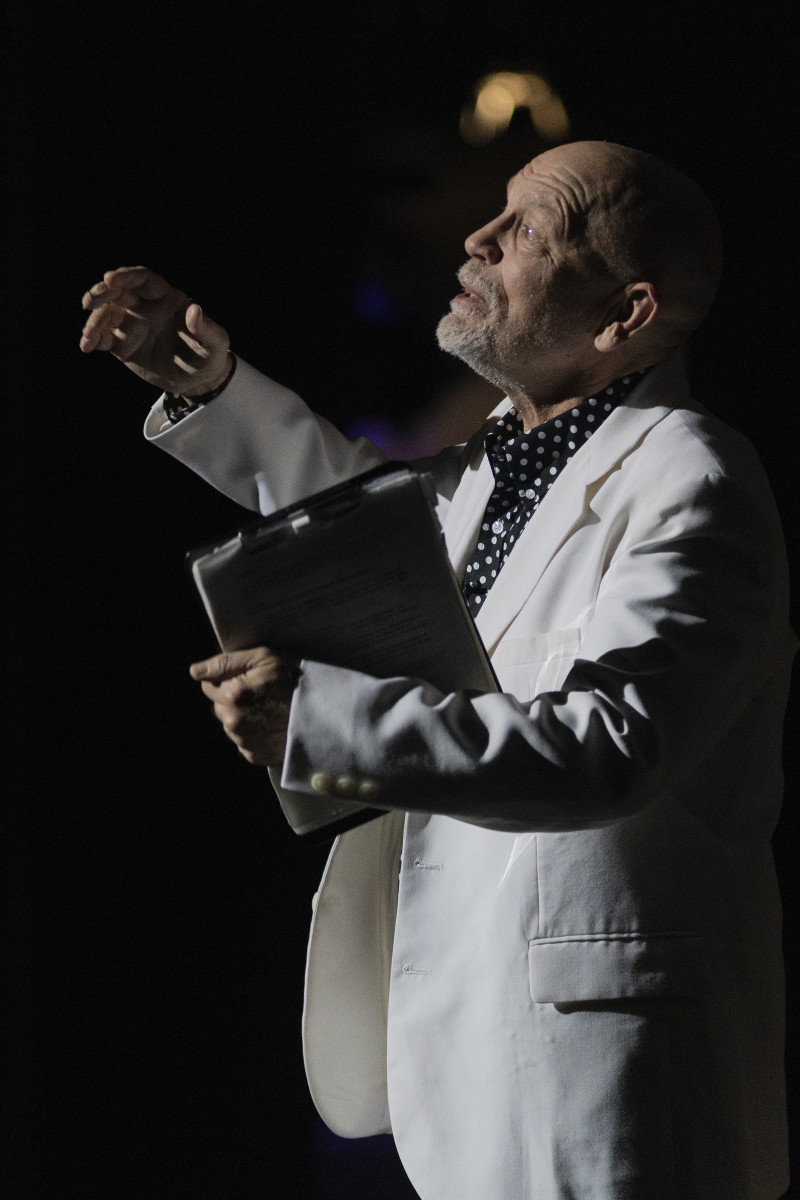

»Please, conductor play and give me some fucking peace«. The mass murderer – and now a writer, as he became one in prison – Jack Unterweger (John Malkovich) demands more »old fashioned music« as he talks about his barbaric actions in the forests of Vienna. We are at Unterweger's book reception. The baroque orchestra Orchester Wiener Akademie sits on stage as witnesses, while Malkovich strangles sopranos Marie Arnet and Theodora Raftis with their underwear to arias by Mozart, Vivaldi and Haydn. Yes, opera is often about men hitting on women.

»I don't usually like this kind of music, it makes me nervous«. Yes, of course, because the baroque music played on period instruments is not just lame background music, but an active narrator which »disrupts« the sales pitch of a monologue, and the repulsive truth that Malkovich wants to share with us – the murder of nine prostitutes. He would rather be a murderer than nothing, he says. But the two singers also make him roll on the ground like a child; he gasps, becomes uncomfortable in his white suit. These moments elevate The Infernal Comedy to more than a clever concept (well-known actor, ok well-known orchestra, authentic murder story). The women gain a glimmer of dignity, while Malkovich's Unterweger loses it. Now what is he without Dandy sunglasses?

The Infernal Comedy was created for Malkovich in 2008, his joker face, his swaying, yes über musical voice. We want to buy his books because evil sells. As a super simple chamber music piece it works. If Malkovich suddenly announced that he now wanted to sing opera, we would also buy a ticket. But how would this story of misogyny sound with the baroque music of 2024?

With her latest album, saxofonist and composer Maria Faust has put the political at the center of jazz, in the long tradition of Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis, Charlie Haden, Fred Frith and Tom Cora, just to name a few. What is surprising is her choice of genre, marches, which is not a per se a traditional jazz form. If Charles Mingus, for instance, payed his tribute to New Orleans marching bands, Faust’s choice is definitely antagonistic. The marches she manipulates and destroys from the inside are not of the entertaining sort, unless you’re a general, as they are of the military and nationalistic kind.

Faust’s score would be a perfect fit for plays like Alphonse Allais’s Père Ubu and Bertold Brecht’s The Resistible Ascension of Arturo Ui, in its use of the grotesque as a creative driving force. Faust’s genius however doesn’t lie in turning these marches into farcical circus fanfares, but in creating a truly threatening space within the music, through chaos but also heart-breaking dissonances, which could be heard as a reminiscence of the wailers mourning their dead fallen in the war. Her fairly large ensemble – seven musicians, plus herself – which is composed of six horns and two drums/percussion creates a perfect harmony-disharmony universe, as if Charles Mingus and Sun Ra had worked together.

Marches Rewound and Rewritten is a seminal and important album which shines darkly in these difficult times and reminds us that everything is political – especially music.

A Seedy Hotel Room Becomes the Stage For Lives, Traumas, and Music

Two chamber operas by Irish composer Emma O’Halloran, both adapted from plays by her uncle, Mark O’Halloran. The first, Trade, is utterly compelling and deeply moving: the story of two men meeting for sex in a grubby hotel room, whose intertwining lives are burdened by trauma and love. The composer writes of the »beautiful economy« in her uncle’s language and the same could be said of her music, which charges the text with more and more tension and urgency without cramping it – but just as often barely registers at all, letting theatre and storytelling rule. The vocal acting is outstanding.

The stylistic resourcefulness of Trade, in which the two characters are so vividly drawn, returns in the monologue Mary Motorhead but with less success. Here, musical sampling can get in the way of our view of the prisoner, who tells of her troubled life before she split her husband’s head open with a knife. Taken with Trade, though, it only emphasizes O’Halloran’s brilliance with theatre and deft musical hand. Would it be too much to hope for one or two truly theatrical, storytelling operas like these in the avant-garde strand of Copenhagen Opera Festival?

From Chaos, Ingebrigt Håker Flaten Weaves Musical Patterns

The keyword for this release can already be found in the title of the opening track: »Deluge (deconstructed)«. Here, Håker Flaten takes a Wayne Shorter composition apart like a LEGO set and reassembles it in a way that only occasionally recalls the original. Out of the pieces emerges a short, repetitive guitar motif, around which drums, saxophones, bass, and piano orbit in increasingly fragmented patterns. The melodies gradually become less concrete, the instruments interact less, the intensity rises almost imperceptibly – until everything falls apart and the process begins again. The same approach is used in the third track, »Kanón (for Paal Nilssen-Love)«, where tension and release unfold in waves that propel the music forward. Håker Flaten masters the art of creating dramatic arcs that guide the listener safely through even the most tumultuous passages.

This is not easy listening – we are still in free jazz territory – but there is a strangely compelling balance between chaos and restraint. At first, one is caught by the surprise of the music’s sudden turns, later by the joy of recognition as one begins to sense where the music sharpens and takes shape.

The album closes with »Austin Vibes (tweaked by Karl Hjalmar Nyberg)«, a noisy collage that slowly opens up toward fragments of more conventional horn melodies. Here we get closest to something resembling a classic jazz feeling—and yet not quite. It is still far from easily digestible music. But even when Håker Flaten and his fellow musicians move furthest into fragmentation, they manage to make the difficult-to-understand surprisingly easy to grasp.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

When Two Worlds Meet: Bro and Takada In Perfect Listening

At last, three years after their concert at the Black Diamond, the collaboration between Danish guitarist Jakob Bro and Japanese percussionist Midori Takada has been released in album format – and it does not disappoint.

Their friendship may seem surprising at first, given their differences, but あなたに出会うまで / Until I Met You reveals how it rests on a shared ability to close their eyes and listen. They give each other space to do what they each do best: Bro’s simple yet refined melodies and Takada’s magical soundscapes. On the title track, Bro sketches the outlines with acoustic guitar and sparse notes, which Takada fills in with shimmering marimba and gong. On A Brief Rest of Sisyphosthe roles are reversed – here Takada sets the frame while Bro adds the details.

The sublime sister pieces Landscape II, Simplicity and Landscape I, Austerity are more abstract than the earlier works. Landscape II breathes hope and longing with resonant chimes and percussion, while a middle section unfolds in melodic harmony between guitar and piano. Landscape I carries the same sense of yearning, but with a more melancholic tone; a gently undulating marimba supports a beautifully moving guitar part. Both pieces radiate a clear sense of respect and tenderness between the musicians: Bro and Takada listen to each other with rare intimacy, and together they have created something truly unique.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek