If John Malkovich could sing, it would be devilish singing

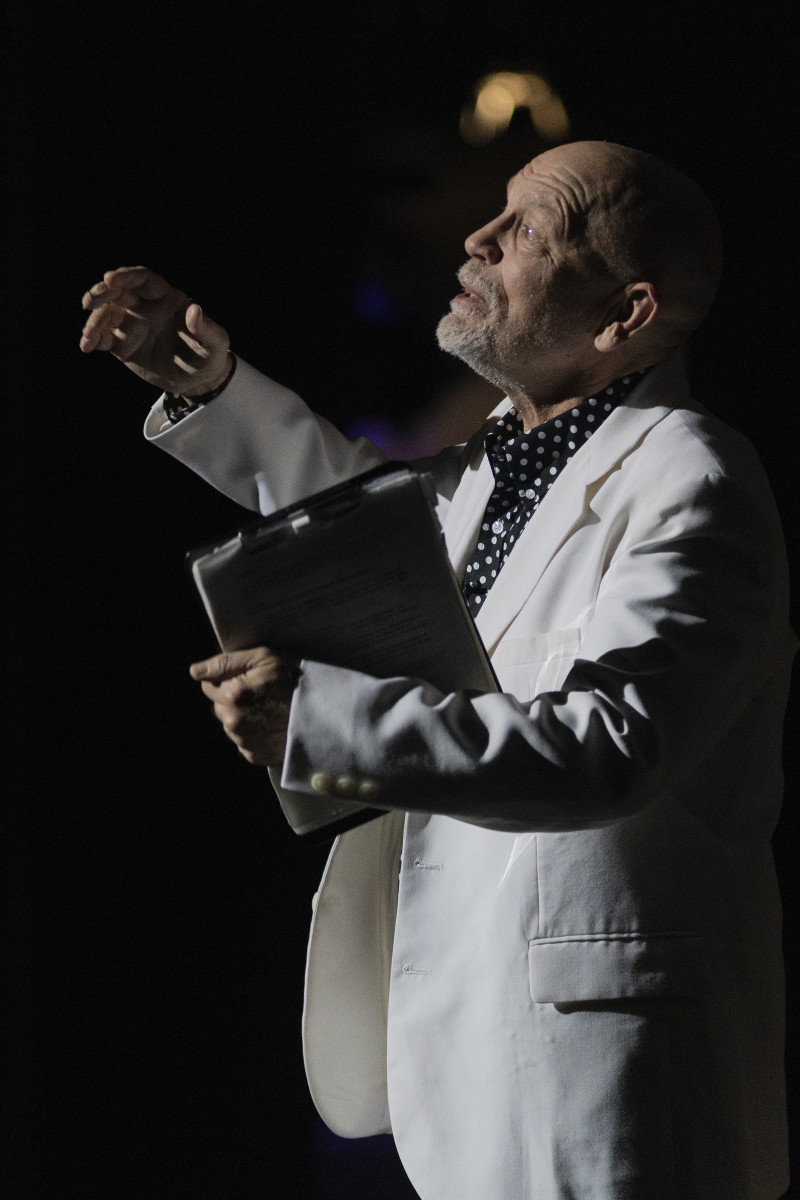

»Please, conductor play and give me some fucking peace«. The mass murderer – and now a writer, as he became one in prison – Jack Unterweger (John Malkovich) demands more »old fashioned music« as he talks about his barbaric actions in the forests of Vienna. We are at Unterweger's book reception. The baroque orchestra Orchester Wiener Akademie sits on stage as witnesses, while Malkovich strangles sopranos Marie Arnet and Theodora Raftis with their underwear to arias by Mozart, Vivaldi and Haydn. Yes, opera is often about men hitting on women.

»I don't usually like this kind of music, it makes me nervous«. Yes, of course, because the baroque music played on period instruments is not just lame background music, but an active narrator which »disrupts« the sales pitch of a monologue, and the repulsive truth that Malkovich wants to share with us – the murder of nine prostitutes. He would rather be a murderer than nothing, he says. But the two singers also make him roll on the ground like a child; he gasps, becomes uncomfortable in his white suit. These moments elevate The Infernal Comedy to more than a clever concept (well-known actor, ok well-known orchestra, authentic murder story). The women gain a glimmer of dignity, while Malkovich's Unterweger loses it. Now what is he without Dandy sunglasses?

The Infernal Comedy was created for Malkovich in 2008, his joker face, his swaying, yes über musical voice. We want to buy his books because evil sells. As a super simple chamber music piece it works. If Malkovich suddenly announced that he now wanted to sing opera, we would also buy a ticket. But how would this story of misogyny sound with the baroque music of 2024?

On his new album, Snowblind, Jacob Kirkegaard shifts his focus away from revealing the hidden sounds of our surroundings to instead depict a psychological drama. The inspiration: The Swedish polar explorer Salomon August Andrée, who in 1897 set course for the North Pole in a hot air balloon – a reckless journey that cost him and two others their lives, blinded by snow and the pursuit of fame.

Through 11 icy tableaus, Kirkegaard paints a portrait of the anxiety and doubt Andrée must have felt when the balloon crashed onto the pack ice east of Svalbard. For two months, the three men continued on foot until they reached the desolate island of Kvitøya – where they died a few weeks later, possibly poisoned by undercooked polar bear meat. By then, nature had long since revealed its hostility.

You hear all this on Snowblind. First, the balloon takes off in an air current that elegantly balances on the edge of suffocating dark synths and a heartbeat rhythm, while a metallic screech – reminiscent of a heroic electric guitar – subtly signals doubt: Was Andrée a hero or a villain? Shortly after, we land in a vast nothingness of scraped metal. The shockwave transforms into mischievous, squelchy synth footsteps as desperation and hallucinations grow: Was that a ship's horn I heard? A lifeline?

But no. Silence wins. The icy water rattles like a hungry beast. The hardboiled psychological drama leaves no room for hope, only a chance to stare at your end right in the face. Had Kirkegaard been a truly ruthless portraitist, we might have descended even further into darkness and disorientation, but his weightless ambience still leaves its marks in the snow.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

We wander through a garden: it's dark, with palms and ferns everywhere, illuminated by infrared light and equipped with sensors, causing the plants to create crackling noise. Red blinking lights above resemble drones. Welcome to the end of the world. And the beginning of the world. We’re not entirely sure. Perhaps it’s a serious rave party that has come to a halt. Just like the techno in the film An Invitation to Disappear, set in a Southeast Asian oil plantation, blurring night and day – making the senses lulled, vulnerable, and compliant.

In the '90s, Erik Satie’s sad piano music always played in broadcasts about climate disasters. Here – at the beginning of a new chaotic year – you can disappear into the exhibition Solarstalgia created by the French-Swiss artist (and Olafur Eliasson student) Julian Charrière. Experience life in an apocalyptic afterworld with all its ominous sounds, in a fully immersive and enveloping way – as this might be how we can learn a bit about the geological forces and changes in nature around us today.

At the end of Arken's long exhibition space, the eye is drawn to an onyx boulder emitting light (the work Vertigo). When approaching something with light, one becomes greedy. The pig-like sounds you hear come from volcanoes in Ethiopia and Iceland. A devouring sound. Just like the entire exhibition, it elegantly addresses both the eyes and techno-loving ears.

It's seriously clammy as you step down into the Cisterns beneath Søndermarken – humid, with brick columns dripping with condensation and chalk stalactites hanging down. A piano has been left down here for five months, slowly deteriorating. I was skeptical about Opløsninger: yet another Annea Lockwood-inspired work, simply inflicting violence on a poor instrument? And if not, is a composer like August Rosenbaum, who works with short, vibe-friendly piano pieces, the right person to elevate the idea into something greater? Yes, as it turns out, fortunately.

Together with visual artist Ea Verdoner, Rosenbaum has created an installation piece that spans three chambers, and in the first, you indeed see the decayed piano with centimeter-thick mold patches on the keys. As you shuffle along to the second chamber, Rosenbaum sits in the dark in front of a better-preserved grand piano. His playing is both minimalist and grandiose, but it’s the breaks in the composition that truly captivate me. Half motifs, repeated triplets, tritone-like intervals. Rosenbaum loops a captured sound from the decayed piano on a sequencer, gets up, and walks away briskly. He returns and turns up the industrial rumble of a gong, as if he were Trent Reznor in the studio. Combined with choreography about duality, a voice-over about life and birth, and a video about the body and decay, it becomes an exciting and reasonably new depiction of the raw, cold, and arbitrary nature of decomposition.

It is rare for an album to be complimented for lulling someone to sleep. But after a month with the album Cymatic by the Swiss-resident, Hong Kong-born Natalja Romine, I have often found myself slipping into dreamland – something I rarely consider a good thing. In the case of Cymatic, however, it is a clear strength. Yanling comes from the world of art music, and the work has already been presented in that context. Still, it stands strong as a piece of cinematic sci-fi ambient. Names like Jean-Michel Jarre, Brian Eno, and Hans Zimmer haunt the album, as modular noise clouds, female vocals, and mysterious electronic pulses and sine waves blend together to create a harmonious tapestry. It is not groundbreaking, and the tracks can be difficult to distinguish from one another. Nevertheless, the captivating piano riffs on »Transmuted« and the gurgling bass synths on »Nebula« stand out. On »Fallen Tempest«, choirs, chords, and reverb coalesce into a higher unity, and on the album's pinnacle, »Aura Nova«, sudden synth stabs threaten to wake one from the dream.

Cymatic is not a masterpiece and can appear on gray days as disposable ambient for a Hollywood blockbuster no one wants to watch. But over time, it grows into a brilliant piece of contemporary art, only suffering from slightly too perfect production and somewhat grandiose gestures. Why get upset over the storm in your teacup if it storms in the right way?

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

With her latest album, saxofonist and composer Maria Faust has put the political at the center of jazz, in the long tradition of Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis, Charlie Haden, Fred Frith and Tom Cora, just to name a few. What is surprising is her choice of genre, marches, which is not a per se a traditional jazz form. If Charles Mingus, for instance, payed his tribute to New Orleans marching bands, Faust’s choice is definitely antagonistic. The marches she manipulates and destroys from the inside are not of the entertaining sort, unless you’re a general, as they are of the military and nationalistic kind.

Faust’s score would be a perfect fit for plays like Alphonse Allais’s Père Ubu and Bertold Brecht’s The Resistible Ascension of Arturo Ui, in its use of the grotesque as a creative driving force. Faust’s genius however doesn’t lie in turning these marches into farcical circus fanfares, but in creating a truly threatening space within the music, through chaos but also heart-breaking dissonances, which could be heard as a reminiscence of the wailers mourning their dead fallen in the war. Her fairly large ensemble – seven musicians, plus herself – which is composed of six horns and two drums/percussion creates a perfect harmony-disharmony universe, as if Charles Mingus and Sun Ra had worked together.

Marches Rewound and Rewritten is a seminal and important album which shines darkly in these difficult times and reminds us that everything is political – especially music.