Om det er ironisk eller passende, at Irma Hünerfauths mekaniske skrotmaskiner fra 70’erne og 80’erne, som lige nu udstilles på Simian, ikke længere virker, må være en smagssag.

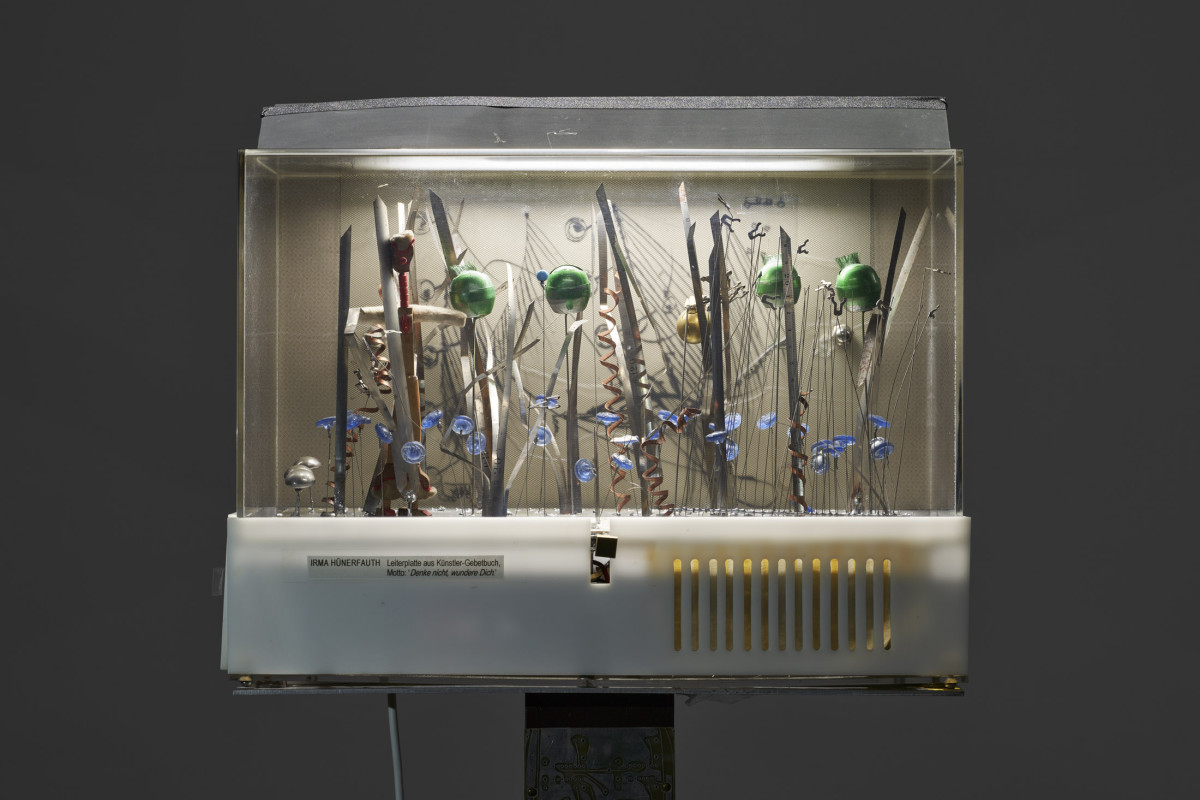

Tyskerens Sprechende Kästen er en satirisk legesyg og spiddende kritik af det accelererende varesamfund, skabt af overflodens egne affaldsprodukter: sammenloddede computerkort, tøjknapper, metalspiraler. I én kasse bræger et får fanget under jorden, i en anden flyver en eroderende sommerfugl af metal hen over en nedbrudt pistol.

Oprindeligt skulle publikum få de ekspressionistiske tableauer til at bevæge sig. »Helft mit!« stod der dengang på udstillingerne. I dag står der, at kunsten ikke må berøres. Så nu står Hünerfauths åbenbart sarte Vibrationsobjekte stille som et unheimlich og melankolsk gravmæle over en socialt indigneret samfundskritik.

I stedet sættes de tilhørende lydspor i gang af sensorer, når man nærmer sig dem hver især. Hurtigt myldrer den gamle cykelkælder derfor med lyde, der bekriger hinanden: en diskant kakofoni af cikader, sfærisk klang, pistolskud og kunstnerens utydeligt hvislende messen om krig, forbrug og tabt natur – det hele oven i hinanden.

Men den tynde lyd er lige så nedslidt som mekanikken, og end ikke en stramt minimalistisk opstilling kan redde udstillingen fra at virke uskarp, uengagerende og en smule meningsløs. Hvor kasserne engang lokkede til interaktion og fordybelse, inviterer de i dag til at stryge direkte ud af det lydlige kaos og over i Field’s.